Due to our compulsion to see patterns everywhere, we’re bad at recognizing true randomness when we see it. At a more fundamental level, we don’t even know if true randomness even exists.

The radioactive decay of the element Americium is used to generate random numbers. A Geiger counter detects the particles emitted through the decay in a pre-set time interval. If the number of particles is even, the device returns a zero, and if it’s odd, it returns a 1. For practical purposes, the resulting string of 0s and 1s is truly random. But is it also random in the sense that if we can never truly predict the decay of individual Americium atoms, no matter how much we know about the universe and how much compute power we have?

Most physicists believe that we can’t and that the universe is truly stochastic. Others aren’t so sure. Einstein didn’t think that God plays dice like that. I’m neither qualified nor motivated to judge the matter, but true randomness seems spooky to me. How does it just materialize? Isn’t its sudden appearance as mysterious as if a particle just popped out of nowhere?

The alternative to true randomness would be that the universe is deterministic. Note that this doesn’t imply that the universe is predictable: As Stephen Wolfram points out, computational irreducibility implies that the only way to compute what happens next is to run the universe.

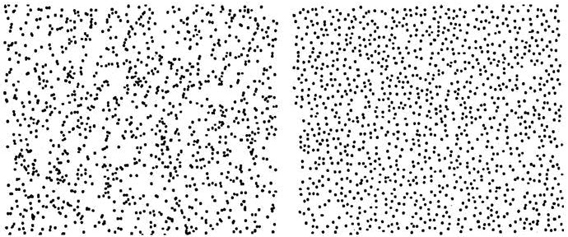

For this reason, whether the universe is stochastic or deterministic isn’t all that important for most of us, but it points to a weakness that is often relevant: Our inability to recognize and accept randomness. We look for patterns everywhere. When confronted with a truly random pattern, we refuse to accept its randomness. This is similar to our inability to accept that sometimes things don’t happen for a reason.

The creators of shuffle features on music playlists like Spotify or iTunes know this. They started off with offering truly random shuffle, but subscribers complained that some songs came up more often than expected. Only once they made the algorithm less random, by making sure that that once a song played, it couldn’t play again for some pre-set time, did the resulting order of songs feel truly random. The sky at night is another example: We look at the stars, and to us they seem clump in constellations. A non-random sky that arranged stars at a certain distance from each other would actually appear more random.